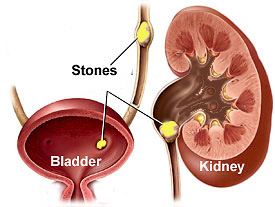

Urinary Stone

5 Key points:

- Kidneys stones can cause severe colicky pain, bloody urine and urine infection

- The kidney can undergo permanent damage if the stone is large and impacted

- Diagnosis is made from ultrasound and xray studies

- Treatment depends on the stone size, site and composition

- Majority of stones can be broken with ESWL, with endoscopy reserved for the large and hard stones

Urinary stones develop in the kidney from a combination of factors, e.g. insufficient water intake, high carbohydrate-low fibre diet, excess oxalates intake (in tea, chocolates) and high purine foods (peanuts, red meat, soya beans, beer).

Symptoms

Most stones present with colicky pain that radiates from the loin to the groin. The pain is so severe that narcotic injections are invariably needed. This pain is due to the high pressures created in the blocked kidney. There is usually noticeable blood in the urine too. Prolonged blockage can lead to infection. Infection manifests as fever, persistent loin pain and painful, frequent urination. If the obstruction is prolonged, the kidney is at risk of permanent damage from pressure atrophy.

Diagnosis

Xrays are needed to confirm the site, size and shape of the stone. A quick screening test is a plain xray (KUB) together with an ultrasound. However, the limitation is that 10% of stones do not show up on KUB because they are either too small or do not contain enough calcium. Also, gas and stool shadows can obscure tiny stones. Hence, xrays using contrast injection (IVU) is the standard way of locating these stones [Fig 1]. The disadvantage with IVU is that bowel preparation is needed, with risk of contrast allergy and it takes 1 hour to do. Hence, non-contrast CT scan is now used to diagnose urinary stones with the advantage that it is fast to perform, needs no bowel preparation or injection of contrast and even tiny, non-calcium containing stones can be imaged [Fig 2].

Fig 1. IVU requires injection of contrast to confirm the stone location

Fig 2. CT scan is fast to do and can even show small radiolucent stones.

Management

Treatment depends on the size and site of the stone. Stones < 4 mm can be managed conservatively because they are small enough to they pass out of the ureter. Stones > 4 mm tend to obstruct, and will require some form of intervention:

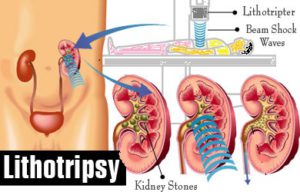

1. ESWL (Shock wave lithotripsy)[Fig 3]

A lithotripter is a machine that stones into tiny pieces using the technology of focused shock waves. The stone is located by means of xray or ultrasound attached to the machine. This is a safe outpatient treatment lasting about 1 hour. It can be used to treat stones lodged in the kidney or ureter, the highest success rate being for kidney stones (> 90%). The patient is awake but will still need intravenous analgesics as at least 3000 to 4000 shocks are given to break the stone. The shock waves do not damage the kidney although the kidney can get swollen or develop a blood clot (subcapsular haematoma). Bloody urine is expected in the following few days. The limitation with ESWL is that it is not suitable for grossly obese patients. The other disadvantage is it is restricted to stones < 2 cm and repeat sessions may be required if the stone is very hard in consistency; such hard stones cannot be predicted from the xrays. Technical limitations are difficulty in localizing the stone in obese patients, and if there is too much bowel shadows overlying the stone.

Fig 3. ESWL treatment to break stones < 2 cm size lodged in the kidney or ureter

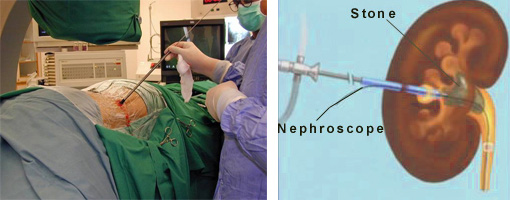

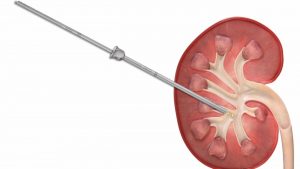

2. PCNL (Endoscopic puncture through the kidney)[Fig 4].

This is a minimally-invasive method for stones > 2 cm located in the kidney or upper ureter. It involves establishing a puncture tract into the kidney to access the stone. A large nephroscope is inserted and the stone broken with a laser, ultrasonic or pneumatic device and the pieces extracted out via this scope [Fig 4a]. The whole procedure is done under xray guidance and can take 2 to 3 hours to do. Hospital stay is at least 3 days. The main risk is excess bleeding that can occur during tract dilatation. About 3% of patients may develop a re-bleed due to an abnormal artery-vein malformation. If so, readmission to hospital for radiographic intervention (angio-embolisation) is needed. Despite the surgical risks, the advantage of PCNL over ESWL is that big, staghorn stones can be cleared with a high success rate ( > 97 %) at a single session.

Fig 4a. PCNL involves a puncture into the kidney to break stones > 2 cm size

A mini-perc [Fig 4b] is also available to treat kidney stones up to 1 cm with the advantage of less trauma and bleeding to the kidney.

Fig 4b. Mini-perc to break kidney stones < 1 cm

3. URS (Ureteroscopy)[Fig 5]

This endoscopic procedure involves a mini-scope that is passed up the urethra into the bladder and up the ureter. It is suitable for stones < 1 cm lodged in the ureter. A flexible ureteroscope can also be used for stones inside the kidney. A Holmium laser or pneumatic probe is used to break the stone. A wired basket can also be inserted to extract the stone pieces. The procedure takes 30 mins to 1 hour and can be done as a day case. Pain and bleeding is usually minor. Some cases may require a double-J stent to be inserted into the kidney, especially if there is any injury to the ureter wall. URS is ideal for stones lodged in the lower ureter with a success rate near 100%.

Fig 5. Ureteroscopy to break stones in the ureter. A flexible type of ureteroscope can also be used for small kidney stones

Summary

Stones can cause severe colic and damage the kidney if the obstruction is not relieved. The diagnosis rests on xrays, the most accurate being the CT scan. Small stones < 4 mm can be managed conservatively, while those > 4 mm are unlikely to pass out on their own and will need to be broken. The safest method is by ESWL, while invasive options using endoscopy ( URS or PCNL ) reserved for the larger and hard stones.