Bladder Cancer

5 Key points:

- Painless bloody urine is the hallmark of bladder cancer

- Most bladder cancers are superficial type, and can be removed with TURBT surgery

- Bladder cancers are prone to recurrences, hence the need for additional chemotherapy or BCG delivered into the bladder after TURBT is done

- Once the cancer has invaded into the bladder muscle, the whole bladder has to be removed

- Should the cancer spread to the lymph nodes, cure is not possible and only chemotherapy can control the disease

Bladder cancer is now the 7th most common cancer in Singapore. Men are affected 3 times more common than women and mostly in those aged above 50 years old. Occasionally, patients as young as 20 years can also get bladder cancer. The causes of bladder cancer are ageing, chemical agents and cigarette smoking.

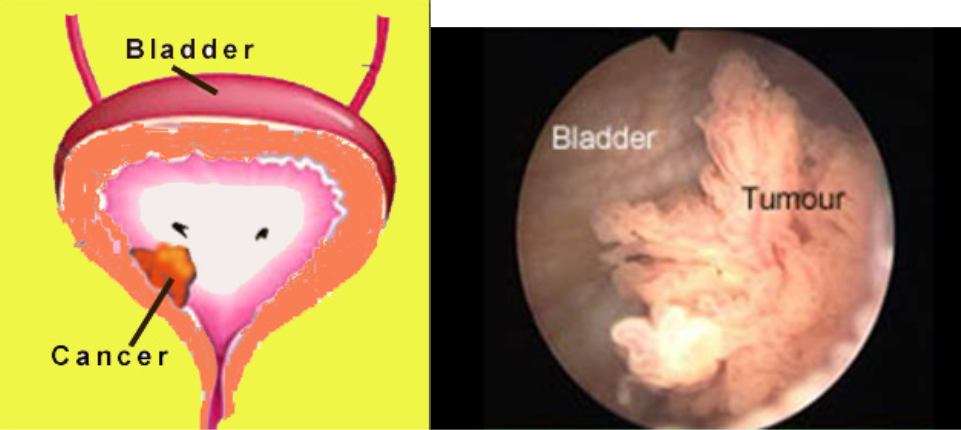

The most common presentation is painless gross haematuria (bloody urine) [Fig 1]. It can also present with irritative bladder symptoms, e.g. frequency and urgency of urination. Quite often, the diagnosis is delayed because the haematuria is intermittent or wrongly attributed to other causes esp. bladder infection.

Fig 1. Blood in the urine is the most common sign

Diagnosis

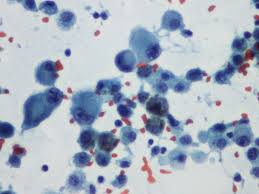

a) Cytology

Although the urine can be sent for cytologic examination to look for presence of cancer cells, its accuracy is limited by low sensitivity (< 50% detection rate) [Fig 2]. Hence, the result is not to be relied on even if it does not show cancerous cells.

Fig 2. Urine cytology showing cancerous cells

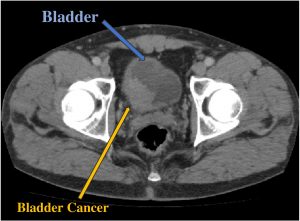

b) Xray

Since haematuria can arise from any part of the urinary tract, the standard initial investigation is an xray called Intravenous Urogram (IVU). It involves the injection of contrast material which is excreted by the kidneys to outline the urinary tract. A bladder tumour may show up as a ‘filling defect’ if the tumour is large enough [Fig 3a]. The CT scan is increasingly being used to diagnose bladder cancer because it is more sensitive and can also stage the cancer, i.e. whether the muscle is invaded, and whether the lymph nodes are involved [Fig 3b].

Fig 3a. IVU showing a huge bladder cancer

Fig 3b. CT scan showing a tumour within the kidney drainage system

Sometimes, the bladder tumour can also be seen on an ultrasound examination if it is > 1 cm [Fig 3c].

Fig 3c. Ultrasound may also detect a bladder tumour if it is > 1cm

A negative IVU or ultrasound does not rule out bladder cancer as small tumours < 1 cm may not be obvious. As such, cystoscopy is mandatory even if the xray or ultrasound does not show any obvious tumour.

c) Cystoscopy

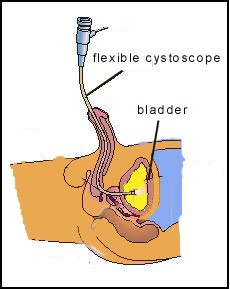

This is easily done under local anaesthesia using a flexible cystoscope [Fig 4]. The advantage is that even flat and small tumours can be seen and biopsy taken to confirm if the tumour is indeed cancerous, as some 5% of bladder tumours are benign.

Fig 4. Flexible cystoscopy is easily done under local anaesthesia

Treatment

i) Early (superficial) Stage

a) Surgery

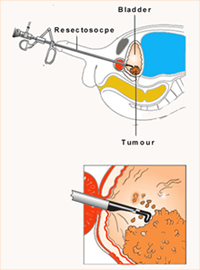

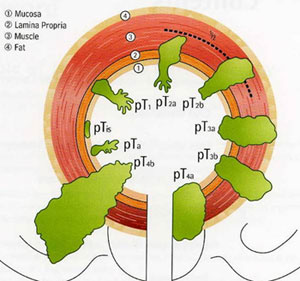

Once the diagnosis of a bladder lesion is confirmed, endoscopic surgery using a resectoscope instrument to cut away the tumour (called TURBT) is the standard treatment [Fig 5]. Bladder biopsies are also taken so as not to miss pre-cancerous areas of the bladder lining (carcinoma-in-situ or CIS). After resecting the tumours, separate muscle biopsies are taken and the bladder is palpated with both hands. General anesthesia is usually preferred and it may take up to 1 hour to resect a large tumour. The pathology report will stage the cancer according to its grade and the depth of invasion [Fig 6].

Fig 5. TURBT to cut away bladder tumour

Fig 6. The staging of bladder cancer

At the time of diagnosis, 80% of bladder tumours are superficial, i.e. confined to the bladder lining. The other 20% are invasive (i.e. penetrated the muscle layer of the bladder). Superficial cancers carry a good prognosis but have a tendency to recur. If they recur frequently, they have a real risk of becoming invasive in the future, especially if the cancer is of high grade or if CIS is present. Invasive tumours will eventually spread to the lymph nodes and distant organs, especially the lungs, bones and liver. Prognosis for invasive disease is poor, hence it is important to treat bladder cancer at its early stage (stage 1) before it invades further into the muscle layer.

After endoscopic tumour resection of superficial bladder tumours, periodic surveillance cystoscopies are needed to pick up recurrences. The regime is 3-monthly for the first year, then 6-monthly to yearly depending on any recurrence. It is important to remember that while bladder cancers may look the same, they may not behave the same.

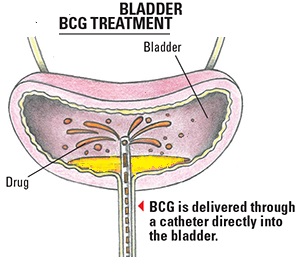

b) Chemotherapy

Those at high risk of recurrence, e.g. large, multiple, high-grade tumours and those with CIS disease are additionally treated with a choice of cytotoxic agents (e.g. Mitomycin C) or immune-enhancing agent (e.g. BCG) instilled into the bladder (intravesical therapy) for 1 to 2 hours respectively [Fig 6]. The treatment protocol is an induction course of 6 doses instilled weekly followed by a maintenance booster of 3 doses instilled weekly every 3 months. BCG is superior in reducing the recurrence rate for tumours that are high-grade and those with CIS disease. However, BCG has more side-effects e.g. fever, haematuria, urgency. Despite its superior efficacy, the current problem is the worldwide shortage of BCG.

Fig 6. BCG is instilled into the bladder to prevent the cancer from recurring

ii) Advanced (Invasive) Stage

a) Surgery

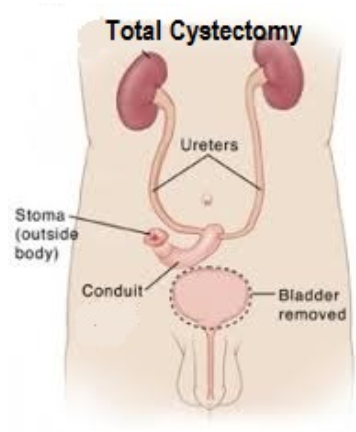

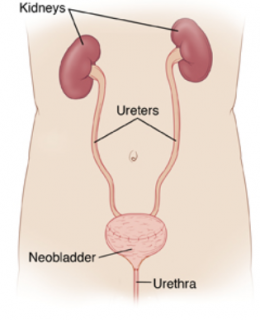

Treatment of patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer is individualised according to the general health status, extent of cancer and personal preferences. Total removal of the bladder (radical cystectomy) for muscle-invasive cancer (Stage 2 and 3) provides the best chance of cure. Partial cystectomy is seldom done as the cancer can recur in the remaining bladder. After a radical cystectomy, the urine from the kidneys and ureters is diverted into a short segment of small bowel (called an ileal conduit) which opens as a stoma on the abdominal wall [Fig 6]. Urine is collected in an external collection bag (urostomy). This type of diversion remains the most popular choice as it is relatively easy to construct. For younger patients, and those who wish to remain continent or avoid a urostomy, a “new bladder” can be constructed using a long segment of intestine. This neobladder is reconnected to the native urethra so that the patient can void normally. Although there is no need to wear an external bag, self-intermittent catheterisation may still be needed as the neobladder may not empty well or become blocked with mucus produced by the intestine lining. Nocturnal incontinence (bed-wetting) is often a problem too. As a neobladder operation is more difficult to do and takes longer to perform, it is reserved more for fit and younger patients.

a)

b)

Fig 7. Following total cystectomy, a) an ileal conduit can be constructed to drain the urine via a short segment of small intestine or b) a neobladder can be fashioned from a longer length of small intestine

b)Radiotherapy

Although radiotherapy is a safer option and allows bladder conservation, the 5 year survival for bladder cancer with muscle invasion is only 20 to 40%. The limitation with radiotherapy is that it may not kill the cancer cells completely and there will be cumulative side-effects on the bladder e.g. frequency, haematuria and incontinence. The radiotherapy has to be delivered daily for a period of 6 weeks.

c)Systemic Chemotherapy / Immunotherapy

Once the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, cure is not possible and only systemic chemotherapy can control such metastatic cancer. This is delivered by the medical oncologist via infusion. Immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors are also showing promise in cases that do not respond to conventional chemotherapy, but these drugs are expensive and may have to given as a combination.

Summary

It is important to detect bladder cancer while it is still at its superficial stage (Stage 1). Treatment consist of TURBT followed by local chemotherapy / immunotherapy instilled into the bladder to prevent recurrences. Once the cancer recurs and invades into the muscle, total cystectomy +/- systemic chemotherapy / immunotherapy is the salvage solution. Hence, the importance that patients do not default on their regular cystoscopies and scans.